I’ve seen several articles recently railing against the very idea of best practices. In this article, I’ll take a closer look at where this criticism is coming from and take it head on.

I recently read a classic executive-targeted article article from CIO.com by Bob Lewis, Why every IT leader should avoid ‘best practices’. His variation on the no-such-thing theme goes as far as suggesting ‘best practices’ are not only flawed, but outright fraud, in what he concludes is “… the enemy of good sense.”

Wow. Nothing like taking a strong stand. I love this approach!

As I read the article, he reveals what is clearly the root of his dislike. He states his position clearly: “…a best practice should be, by definition, a practice that can’t be improved on”. This appears to be the heart of his anti-best practice argument: The belief that Merriam-Webster arbitrates the meaning of terms and how they’re used. That the word “best” intrinsically means “universally best, for everyone, in all circumstances”, and when combined with ‘practice’, can only reasonably mean it’s mic drop game over time.

This is a flawed view of the meaning and application of ‘best practice’

He then gives three distinct criticisms of “best practices” as a concept:

- Argument by assertion

- Best is contextual

- Stasis over innovation

While I agree there are many organizations for whom these criticisms apply, it’s hardly an indictment of the concept of “best practice” itself – only of their incorrect usage.

Let’s take a closer look.

Argument by assertion

It’s reasonable to ask “who says a best practice is ‘best’”? Any competent CIO must challenge any outside advice, because ultimately they are accountable for results in their organization.

But watch the author’s logic unfold here. He is criticizing an assertion because it’s not based on “evidence and logic”… and then goes on to offer no evidence or logic outside his own asserted opinion.

See the problem?

Where’s his supporting evidence? What data does he offer? Where’s the research findings?

Remember – the article is advice for “every IT leader”. (every IT leader, in every organization)

Best is contextual

The author’s next criticism is that what’s “best” is always in the context of the organization itself.

With this I wholeheartedly agree!

I always advise IT leaders to solve the problems they have – not the ones others have (or they wish they had!). They should first understand the culture and context of their organization and work to deliver meaningful results.

Which is easier said than done, in practice, because the modern organization faces a constantly changing set of circumstances.

Enter the field of Complexity.

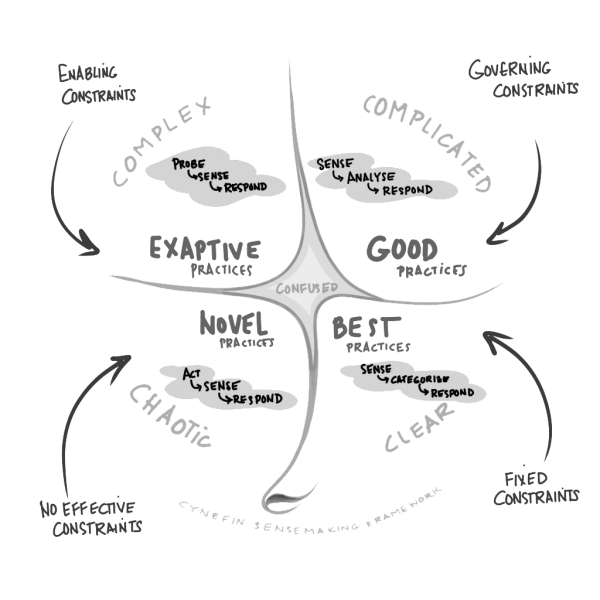

I’m most familiar with Cynefin – the brainchild of Dave Snowden which seeks “…to help leaders understand their challenges and to make decisions in context. By distinguishing different domains (the subsystems in which we operate), it recognizes that our actions need to match the reality we find ourselves in through a process of sense-making.”

The thoroughly researched, peer-reviewed and constantly evolving framework describes a number of contexts – and recommends actions and practices optimized for that particular context.

As shown in the diagram above (taken directly from The Cynefin Company’s website), the lower right domain is described as “stable, and the relationship between cause and effect is clear: if you do X, expect Y.”

In this domain, best practices are warranted.

But as you go counter-clockwise, the recommended practices move from best, to good, to exaptive and to novel. This is a critically important element of complexity – that we must be cognizant of, and adaptive to the context in which we find ourselves.

Stasis over innovation

What complexity helps us understand is that there are no practices (poor/good/better/best) that apply to all contexts. This is fundamental for leaders who must guide their organizations through challenging circumstances.

It’s worth pointing out that at any given moment, an organization may be in multiple domains simultaneously, and must seek to act in dynamic and adaptive ways to optimize likelihood of good outcomes.

Further, leaders cannot afford to presume that a context will remain static for any length of time. The practices that were appropriate and effective yesterday may be a hinderance today.

Appropriate actions are always contextual.

When, not if

As shown in the Cynefin model above, the left side (complex and chaotic) is where you focus your innovative energies to solve incredibly complex and challenging situations. New, novel and emerging practices come from these circumstances – and may over time become best practices.

For what it’s worth, Merriam-Webster describes best practices as:

“a procedure that has been shown by research and experience to produce optimal results and that is established or proposed as a standard suitable for widespread adoption”

Under this definition – and in the clear domain – best practices can be incredibly helpful. They can be easily adopted and made to fit the organization with limited investment of costly and scarce engineering resources. The connection between cause and effect is clear, and (best) practices shown by “research and experience to produce optimal results” are quite appropriate.

No need to reinvent the wheel.

But where circumstances are complex, the connection between cause and effect can only be determined in retrospect; the result of experimentation.

This is NOT a place to apply best practices.

So, the real issue behind the anti best practices energy – and I see it quite often – is the tendency toward ‘one-size-fits-all’.

- Zealous practitioners who act as if best practices are the cure for all ills, and

- Those who advise against best practices altogether

Both miss the real point that IT leaders must develop the ability to rapidly assess what domain they’re operating in at any point of time, and apply practices appropriate to that challenge.

One comment on „Who said Best Practices are best for everyone?”

Comments are closed.